Half the land in Oklahoma could be returned to Native Americans. It should be.

A Supreme Court case about jurisdiction in an obscure murder has huge implications for tribes.

By Rebecca Nagle, The Washington Post

Rebecca Nagle is a writer, advocate and citizen of Cherokee Nation living in Tahlequah, Okla.

The Washington Post article

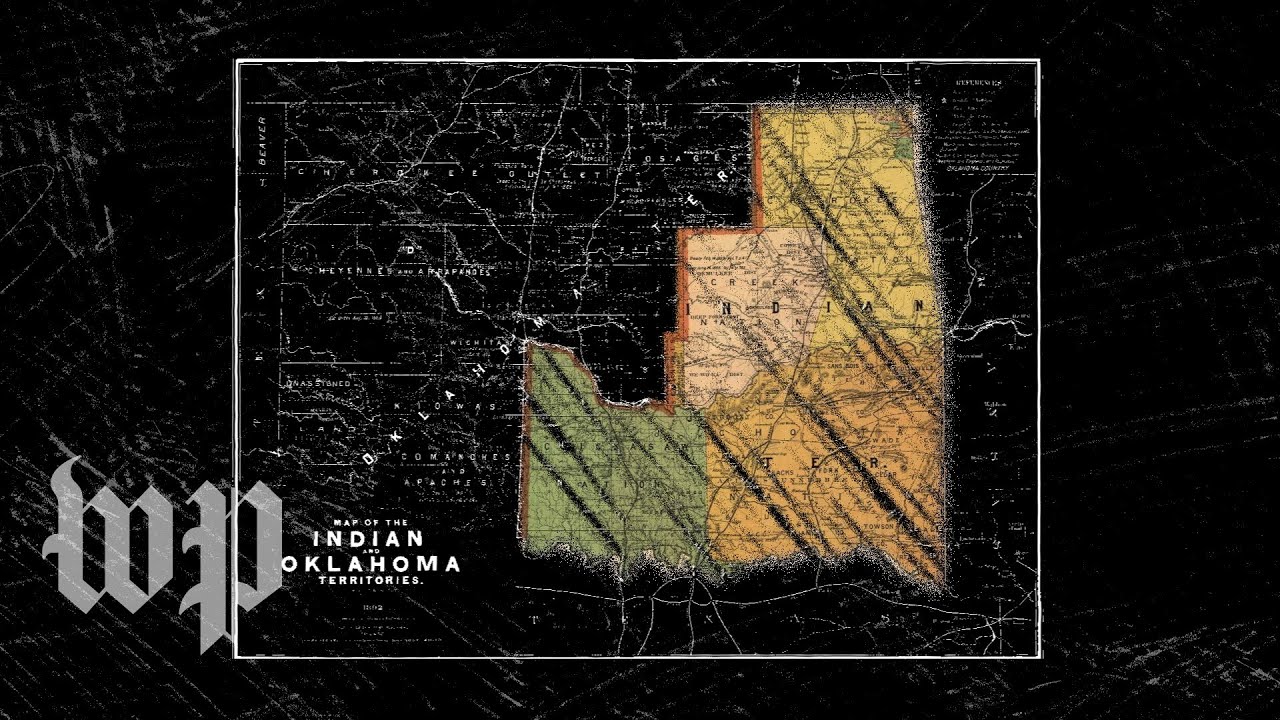

How a murder could reshape Oklahoma. A Supreme Court case could have huge implications for American Indian reservations and state rights. (Luis Velarde /The Washington Post)

The fight for Native American humanity. In 1879, a landmark case asked the question: Are Native Americans considered human beings under the U.S. Constitution? This is Chief Standing Bear's story. (The Washington Post)

article

On the morning of June 22, 1839, the Cherokee leader John Ridge was pulled from his bed, dragged into his front yard and stabbed 84 times while his family watched. He was assassinated for signing the Cherokee Nation’s removal treaty, a document that — in exchange for the tribe’s homelands — promised uninterrupted sovereignty over a third of the land in present-day Oklahoma. That promise was not kept.

Sixty-seven years later, federal agents questioned John’s grandson, William D. Polson. They needed to add him to a list of every Cherokee living in Indian Territory to start the process of land allotments. Through allotment, all land belonging to the Cherokee Nation — the land John had signed his life for — would be split up between individual citizens and then opened up for white settlement. And by this grand act of bureaucratic theft, Oklahoma became a state.

Today, on the same plot of earth where my great-great-great grandfather John Ridge still lies, is a small cemetery holding five other generations of my family. When I am buried, I will be the seventh. While the cemetery is surrounded by our allotment land and a cousin lives next door, none of it is Cherokee land.

Land loss for Native Americans is framed as a historic phenomenon, but for tribes in Oklahoma, it never stopped. Through allotment, the Cherokee Nation lost 74 percent of our treaty territory. Today, we still lose land every time an acre is sold to a non-Indian, inherited by someone less than half blood quantum, or even when an owner lifts restrictions to qualify for a mortgage. After a century of the legal status quo, the Cherokee Nation has jurisdiction of only 2 percent of our land left after allotment. While the initial hemorrhage of land loss occurred in previous centuries, we are still bleeding.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that could make the bleeding stop.

On Aug. 28, 1999, on a rural road outside Henryetta, Okla., Patrick Murphy murdered fellow Creek citizen George Jacobs. He was tried and sentenced to death. In 2004, Murphy’s public defender argued that the crime occurred within Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation and — because only tribes and the federal government can prosecute crimes on Indian land — the state of Oklahoma did not have jurisdiction to try the case. In 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit agreed. Oklahoma appealed, and now the outcome of Murphy v. Carpenter affects not only the fate of one man but the treaty territory of five tribes and nearly half the land in Oklahoma.

The history of tribal land, with small exceptions, has moved unforgivingly in one direction. Today, American Indian reservations comprise only 55 million acres, or 2 percent of all land in the United States. Meanwhile, the National Forest Service occupies 200 million acres. In the emergence of this great nation, our government set aside more land for trees than for Indians.

If the Supreme Court upholds the 10th Circuit’s decision, the ruling would result in the largest restoration of tribal jurisdiction over Native land in U.S. history.

The undisputed fact of the case is that Oklahoma does not have jurisdiction if the murder occurred on reservation land. The disputed fact, and the question brought before the court yesterday, is “whether the 1866 territorial boundaries of the Creek Nation . . . constitutes an ‘Indian reservation’ today.”

Creek citizens arrived in present-day Oklahoma at gunpoint. Their treaty territory — along with the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws and Seminoles — was promised to them “as long as the grass grows or the water runs.” Yet, at the turn of the century, the government came, divided up that interminable land, and gave one parcel to each tribal citizen. Most of the allotted land quickly transferred to white ownership — by sale, by swindle or by outright theft.

Between 1893 and 1907, the federal government took many different actions to force allotment on tribes. They threatened and coerced tribal leaders. They jailed traditionalists who refused to participate. They took over schools, courts, mineral resources and even the dispersal of tribal funds.

Amid the furious land grab, one important action Congress did not take was to legally terminate Creek Nation’s reservation. According to the Supreme Court decision Solem v. Bartlett, reservations cannot be terminated without a “clear statement” from Congress. That statement, in the historical record, simply does not exist.

Oklahoma’s position is that no such statement is needed because the sheer and devastating totality of “everything [that] was taken away from tribes,” as the state’s lawyer argued, is indication enough that Congress intended to leave them with nothing, much less a reservation, and “not one single absolute smidgen” of sovereignty over their land.

Sixty-seven years later, federal agents questioned John’s grandson, William D. Polson. They needed to add him to a list of every Cherokee living in Indian Territory to start the process of land allotments. Through allotment, all land belonging to the Cherokee Nation — the land John had signed his life for — would be split up between individual citizens and then opened up for white settlement. And by this grand act of bureaucratic theft, Oklahoma became a state.

Today, on the same plot of earth where my great-great-great grandfather John Ridge still lies, is a small cemetery holding five other generations of my family. When I am buried, I will be the seventh. While the cemetery is surrounded by our allotment land and a cousin lives next door, none of it is Cherokee land.

Land loss for Native Americans is framed as a historic phenomenon, but for tribes in Oklahoma, it never stopped. Through allotment, the Cherokee Nation lost 74 percent of our treaty territory. Today, we still lose land every time an acre is sold to a non-Indian, inherited by someone less than half blood quantum, or even when an owner lifts restrictions to qualify for a mortgage. After a century of the legal status quo, the Cherokee Nation has jurisdiction of only 2 percent of our land left after allotment. While the initial hemorrhage of land loss occurred in previous centuries, we are still bleeding.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that could make the bleeding stop.

On Aug. 28, 1999, on a rural road outside Henryetta, Okla., Patrick Murphy murdered fellow Creek citizen George Jacobs. He was tried and sentenced to death. In 2004, Murphy’s public defender argued that the crime occurred within Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation and — because only tribes and the federal government can prosecute crimes on Indian land — the state of Oklahoma did not have jurisdiction to try the case. In 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit agreed. Oklahoma appealed, and now the outcome of Murphy v. Carpenter affects not only the fate of one man but the treaty territory of five tribes and nearly half the land in Oklahoma.

The history of tribal land, with small exceptions, has moved unforgivingly in one direction. Today, American Indian reservations comprise only 55 million acres, or 2 percent of all land in the United States. Meanwhile, the National Forest Service occupies 200 million acres. In the emergence of this great nation, our government set aside more land for trees than for Indians.

If the Supreme Court upholds the 10th Circuit’s decision, the ruling would result in the largest restoration of tribal jurisdiction over Native land in U.S. history.

The undisputed fact of the case is that Oklahoma does not have jurisdiction if the murder occurred on reservation land. The disputed fact, and the question brought before the court yesterday, is “whether the 1866 territorial boundaries of the Creek Nation . . . constitutes an ‘Indian reservation’ today.”

Creek citizens arrived in present-day Oklahoma at gunpoint. Their treaty territory — along with the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws and Seminoles — was promised to them “as long as the grass grows or the water runs.” Yet, at the turn of the century, the government came, divided up that interminable land, and gave one parcel to each tribal citizen. Most of the allotted land quickly transferred to white ownership — by sale, by swindle or by outright theft.

Between 1893 and 1907, the federal government took many different actions to force allotment on tribes. They threatened and coerced tribal leaders. They jailed traditionalists who refused to participate. They took over schools, courts, mineral resources and even the dispersal of tribal funds.

Amid the furious land grab, one important action Congress did not take was to legally terminate Creek Nation’s reservation. According to the Supreme Court decision Solem v. Bartlett, reservations cannot be terminated without a “clear statement” from Congress. That statement, in the historical record, simply does not exist.

Oklahoma’s position is that no such statement is needed because the sheer and devastating totality of “everything [that] was taken away from tribes,” as the state’s lawyer argued, is indication enough that Congress intended to leave them with nothing, much less a reservation, and “not one single absolute smidgen” of sovereignty over their land.

The attorney for Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Riyaz Kanji, rebuked this analysis, giving examples from tribes who, despite federal infringement, still clearly have reservations. “Congress has told the tribes over time . . . you will allow this mining and these easements along your land, even if you don’t want it. You will allow your children to be taken away and placed in boarding schools, even if no parent would want that.” Maltreatment alone, Kanji argued, does not dissolve a reservation.

More than 100 Indian reservations went through allotment, and arguably every tribe has had something — whether land, children, money, books or papers — seized by the United States or their surrounding state. If such hostile actions alone can be evidence to the Supreme Court that a reservation no longer exists, tribes could lose land without their or even Congress’s consent. In short, it would set unique and dangerous precedent that merely treating Native Nations as though their land does not belong to them is enough to take it away.

Oklahoma argued yesterday that the sky is falling down, and if the 10th Circuit decision is upheld, it will cease to function as a state — a compelling argument for people who know nothing about how reservations legally function. An entire body of law already governs states’ relationships to tribes and those tribes’ relationship to non-Indian residents. Half the states in the union have reservations, and the majority of those have reservations that — thanks to allotment — have non-Native owned “fee land” where tribal jurisdiction is already limited. Reservations comprise 27 percent of the land in Arizona, and it functions just fine.

The exact legal question presented by this case — whether the allotment of tribal land dissolved a reservation — was asked and answered by the Supreme Court less than two years ago. In 2016, eight of the nine justices ruled in favor of the Omaha Tribe, and five of those justices are still on the bench. But the disputed area the Supreme Court upheld for the Omaha Tribe is much smaller, has fewer non-Native residents, and lacks the vast oil and gas reserves compared to 40 percent of the state of Oklahoma. If Oklahoma wins, the obvious reason will be the only difference between the two cases: circumstance, not precedent.

More than 100 Indian reservations went through allotment, and arguably every tribe has had something — whether land, children, money, books or papers — seized by the United States or their surrounding state. If such hostile actions alone can be evidence to the Supreme Court that a reservation no longer exists, tribes could lose land without their or even Congress’s consent. In short, it would set unique and dangerous precedent that merely treating Native Nations as though their land does not belong to them is enough to take it away.

Oklahoma argued yesterday that the sky is falling down, and if the 10th Circuit decision is upheld, it will cease to function as a state — a compelling argument for people who know nothing about how reservations legally function. An entire body of law already governs states’ relationships to tribes and those tribes’ relationship to non-Indian residents. Half the states in the union have reservations, and the majority of those have reservations that — thanks to allotment — have non-Native owned “fee land” where tribal jurisdiction is already limited. Reservations comprise 27 percent of the land in Arizona, and it functions just fine.

The exact legal question presented by this case — whether the allotment of tribal land dissolved a reservation — was asked and answered by the Supreme Court less than two years ago. In 2016, eight of the nine justices ruled in favor of the Omaha Tribe, and five of those justices are still on the bench. But the disputed area the Supreme Court upheld for the Omaha Tribe is much smaller, has fewer non-Native residents, and lacks the vast oil and gas reserves compared to 40 percent of the state of Oklahoma. If Oklahoma wins, the obvious reason will be the only difference between the two cases: circumstance, not precedent.

In 1835, the Supreme Court upheld the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation against the state of Georgia in a landmark decision that effectively ended Andrew Jackson’s campaign to remove all Indians west of the Mississippi. That was, until Jackson simply ignored the decision. He famously remarked, “Marshall has made his decision, let us see him enforce it.” As a result, Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws and Seminoles were rounded up by U.S. soldiers and forced on death marches in which a quarter to a third of their citizens died.

When Jackson vowed to defy the Supreme Court, there was one other man standing in the room. It was my ancestor, John Ridge.

I am not telling the story of my family and my tribe to ask the Supreme Court to change the law. I tell this story to ask that the law be followed.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the land that John Ridge not only died on, but for, could be acknowledged as Cherokee land for the first time in more than 100 years. John signed the treaty of New Echota knowing he would be killed for it but believing that the rights of the Cherokee Nation enshrined in that blood-soaked document were worth it.

One hundred and seventy-nine years later, the grass is still growing, the water is still running and, in eastern Oklahoma, our tribes are still here. And despite the grave injustice of history, the legal right to our land has never ended.

When Jackson vowed to defy the Supreme Court, there was one other man standing in the room. It was my ancestor, John Ridge.

I am not telling the story of my family and my tribe to ask the Supreme Court to change the law. I tell this story to ask that the law be followed.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the land that John Ridge not only died on, but for, could be acknowledged as Cherokee land for the first time in more than 100 years. John signed the treaty of New Echota knowing he would be killed for it but believing that the rights of the Cherokee Nation enshrined in that blood-soaked document were worth it.

One hundred and seventy-nine years later, the grass is still growing, the water is still running and, in eastern Oklahoma, our tribes are still here. And despite the grave injustice of history, the legal right to our land has never ended.

Half the land in Oklahoma could be returned to Native Americans. It should be.

A Supreme Court case about jurisdiction in an obscure murder has huge implications for tribes.

By Rebecca Nagle, The Washington Post

Rebecca Nagle is a writer, advocate and citizen of Cherokee Nation living in Tahlequah, Okla.

The Washington Post article

read further...

By Rebecca Nagle, The Washington Post

Rebecca Nagle is a writer, advocate and citizen of Cherokee Nation living in Tahlequah, Okla.

The Washington Post article

read further...

PHLASK Project - find water map

The PHLASK Project was conceived as a social enterprise solution to help make an existing system - accessing and drinking water - more ecologically sustainable.

The mission of the project was to reimagine how existing infrastructures and systems could be reorganized and optimized to reduce waste and provide greater access to water, simply by re-engineering the social norms of accessing existing water sources.

by Billy Hanafee

Find water map

read further...

The mission of the project was to reimagine how existing infrastructures and systems could be reorganized and optimized to reduce waste and provide greater access to water, simply by re-engineering the social norms of accessing existing water sources.

by Billy Hanafee

Find water map

read further...

North Philly Teach-in: Changing the Master Narratives, November 10, 2018, Mount Pleasant Mansion, By Denise Valentine

North Philadelphia has undergone rapid and significant changes over the last 2-1/2 centuries. While facing a history of discriminatory housing policies, strategic decay and displacement, African-Americans have raised families, created community, made their mark and changed the course of history. In recent decades, archival material has been uncovered revealing the lives of Africans enslaved at several Fairmount Park Mansions. What are their stories? If we don't remember them who will? If we don't tell these stories who will? And, who will remember us when we are gone?

read further...

read further...

This App Can Tell You the Indigenous History of the Land You Live On

Whose land are you on? Start with a visit to native-land.ca. Native Land is both a website and an app that seeks to map Indigenous languages, treaties, and territories across Turtle Island. You might type in New York, New York, for example, and find that the five boroughs are actually traditional Lenape and Haudenosaunee territory.

read further...

read further...

Sanctuary Directory

The Sanctuary Directory, compiled by PHLA collaborators is showing different community partners included: The Attic Youth Center, Project SAFE, Prevention Point, Laos in the House, New Sanctuary Movement, Broad Street Ministry and other organizations on sanctuary related services throughout the city.

read further...

read further...